![[Item #57897] Archive of correspondence to their son Robert and daughters-in-law Blair Cowley and Susan Cheever, 1957-1970. Malcolm COWLEY, Muriel.](https://lornebair.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/57897.jpg?auto=webp&v=1713198913)

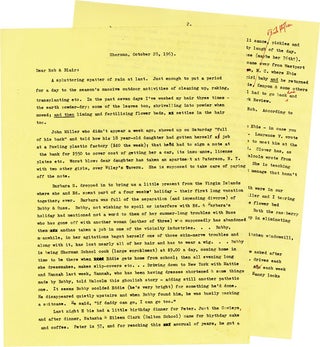

Archive of correspondence to their son Robert and daughters-in-law Blair Cowley and Susan Cheever, 1957-1970

Palo Alto, CA; Rome; Holllins, VA: 1957-1970. A small but substantial archive of Cowley family correspondence, comprised of 44 items (38 letters and six post cards) on 56 pages, mostly 4to, various places (Palo Alto, CA; Rome; Hollins College) but primarily from the Cowleys' principal residence in Sherman, CT. All addressed to their son Robert and his wives, first Blair, and then Susan (Cheever), Nov. 30, 1957 – Sept. 17, 1970. 23 letters and all 6 post cards are in Muriel's hand, the remaining 15 letters in Malcolm's, though almost all of the letters are written as from both parents. All the letters are in Very Good to Fine condition, many with original mailing envelopes. Also included are five retained carbons of letters from Robert to Malcolm, and six miscellaneous items including the engraved invitation to Robert and Susan Cheever's wedding as well as notes from Robert's children and first wife Blair.

An extensive, widely informative and intensely personal series of letters from the Cowleys to their son and daughters-in-law concerning their daily lives, their extended family, their literary friends and academic associates. There are numerous passing references to friends of the Cowleys, especially literary friends like Allen Tate, Conrad Aiken, Glenway Wescott, Van Wyck Brooks, James Thurber, Robert Coates, Mark Van Doren, Wallace and Mary Stegner, Josephine Miles, Ramon Guthrie, Kenneth Burke, Joseph Campbell, Alexander (Sandy) Calder, among many others, with, not surprisingly, news of the vicissitudes of this aging and ailing generation of writers.

Robert Cowley, an editor and a military historian, married Susan Liley Cheever, the daughter of John Cheever, in May of 1967; they divorced in 1975. Muriel’s letters to Robert, which understandably make up the larger portion of the correspondence, are often concerned about domestic or family matters but encompass the Cowleys personal and academic lives together, and often refer to their friends and acquaintances, while her husband’s letters are more often concerned about his own literary life, and comments on the world at large. For instance, in one particularly pointed letter written on July 22,1968, Muriel appears to criticize her son, asking” “Whatever has changed you so drastically – you who were never cruel, bitter or mean.” In the same letter, she mentions the death of Allen and Helen Tate’s twin son Michael: “Wednesday morning shortly after Malcolm had left for New York, came a phone call from Tennessee from Allen Tate. One of his twins, Michael (the smaller) had died the night before. He’d choked to death on a toy while being bathed by a reliable woman. Helen and Allen were six miles away, dining with friends at the time. Michael had been in perfect health. The news was so shocking I could scarcely speak. Tears rolled down my cheeks. It was so horrible, there were no words for it. Allen & Helen loved those babies – less than a year old. Allen helped with their feeding and care, and recently, with great strategy . . . had moved to Monteagle, Tenn. Where the Tates had built a new house last summer. That this nasty trick of fate should have befallen the Tates is still unbelievable. Helen frequently absented herself from parties, lectures, a “do” at the Institute, if she didn’t have the right person to care for the little boys.” In a later letter, dated Feb. 24, 1970, she asks: “Did we write you that Helen and Allen Tate had a new little boy shortly before Christmas?” [It is perhaps noteworthy that Tate was 70 at the time.]

Malcolm’s letters, generally longer and more discursive, are noteworthy for their observations on other writers and the state of the world. The following represent a small sample of them: On Nov. 6, 1960, Malcolm comments on the 1960 Presidential race: “It’s hard to vote for Nixon after looking a few times at his picture, which might be that of Uriah Heep. We sent off our absentee ballots in good time.” In a long letter from Malcolm on Dec. 10, 1960, he writes about life at Stanford and their experience with (or without as the case was) C. P. Snow and Pamela Hansford Johnson: “The night before we’re having the writing class, all thirteen of them and six of the wives, to dinner here to meet C. P. Snow and Pamela Hansford Johnson, that is, if the Snows don’t duck out on us.” The next day, Muriel writes, and mentions that, indeed, without “a word to anybody”, the Snows did not come to the dinner party but instead “flew off to Washington!” Several days later, on Dec. 14, Muriel reports that the Snows had returned to Berkeley, and that “Friends who had heard him (Snow) lecture at Columbia on this trip said that Sir Charles looked played out. Malcolm more than agreed that he and His Lady had better take it easy and get some rest and not come to our party.” The Kennedy Inauguration: Muriel writes on January 20, 1961: “How we wish we’d had TV to view the Washington goings-on. A most terrible moment for Robert Frost while reading his introductory remarks. For a few moments I thought the poor old man was having a stroke but it turns out the sun was shining on the paper from which he was reading. When he said his poem, his voice came through strong and firm as when he was here during election week. . . . Carl Sandburg is in Los Angeles; will be at Berkeley on Saturday. His nose must truly be out of joint over Frost’s having been given first place in the literary inaugural line-up.”

On March 2, 1961, Malcolm mentions his heavy work schedule: “The Stanford tour of duty is drawing to a close. Three weeks more. My schedule has been easier in the winter quarter; no big lecture course; only a four-hour writing course and a four-hour graduate seminar. So of course I got involved in outside activities: a public lecture at Stanford, one at Utah, and one at Davis, which is one of the six or seven campuses of the University of California; an article for the Reporter, ditto for the Saturday Review, and some miscellaneous editing for Viking. I’ve been working like a junkman’s horse ever since we got here. . . Mostly I read and hammer away on the typewriter.” On Aug. 26, 1969, Malcolm comments on the Woodstock Festival: “I can’t fill you in with What’s Happening; I only know what I read in the Times. Frinstance the Woodstock Festival, which attracted some 400M hippies, all smoking pot, some on harder drugs, some wandering around naked in the rain. Jesus, what goings on. We even had a representative from Sherman . . . who wrote an enthusiastic report for the Sentinel.”

On Nov. 3, 1969, Malcolm comments on the death of Kerouac: “Did you read that Jack Kerouac defuncted at 47? Apparently he died of drink; he should have stuck to pot. He had a natural talent for writing, for the flow of words, that would have produced admirable results if it had been directed by simple good sense. Beside him Allan (sic) Ginsburg (sic) seems as wise as Buddha.” On Nov. 28 1969, Malcolm comments on the “Pinkville” or My Lai massacre: “The Pinkville massacre. The newspapers are a little hesitant to comment because people are going to be tried for murder and the courts have gotten strict about newspaper comments that might weaken the case of defendants. But I think the shock is deep – why here we are as bad as the Nazis at Lidice and Oradour – and I think that eventually the Pinkville massacre will do more to propel us out of Vietnam than anything else that has happened. So those babies and pregnant women and old men won’t, in the horrible phrase, have died in vain.”

On June 28, 1970, Malcolm writes: “The world lurches along as after five martinis. Reading the NY Times is like reading clinical reports from the staff of an asylum. For hopeless cases: the diagnosis is dementia precox (sic) with paranoid symptoms. Some of the patients have a pattern in their madness: for instance, the Nixon administration is going to be consistently against universities, consistently against intellectuals (and even against printed matter), consistently against conservation. Note the cut in appropriations for education . . . Note the impending rise in postal rates . . . Note the recent executive order that opens the national forests to more lumbering. . . . There are rumblings of trouble in the publishing world. Atheneum sold itself to a conglomerate. Harpers fired the trade-book editor-in-chief after trouble all down the line. Fantastic advances to authors in the news contributed to the trouble; Harvey Segal, an adviser at Harpers, says that there is a $400M outstanding on one book of which the manuscript hasn’t been delivered. Harper stock fell from 80 to 10, just like stock in the Penn Central.”.

Price: $15,000.00